How the Documentary Free Chol Soo Lee Brought Asian American History Full Circle

Ada Tseng offers us a moving inside perspective behind the story of the Emmy Award–winning documentary Free Chol Soo Lee. Ada is a runner, karaoke lover, and longtime journalist covering Asian American culture. She recently published a book with co-author Jon Healey called Breaking into New Hollywood: A Career Guide to a Changing Industry. Please enjoy our conversation!

Tiên Nguyễn: What is your favorite story to tell about Asian American history?

Ada Tseng: My favorite story is the story of Chol Soo Lee. Not only his story and the Free Chol Soo Lee movement that led to his freedom in the early 1980s, but also the story of how the documentary about him came together 40 years later.

This really integral moment in Asian American history had kind of been lost a little bit. People didn't know about it. But filmmakers/journalists Julie Ha and Eugene Yi brought the story back, by turning it into a documentary in 2022.

And then it won an Emmy. So I feel like the entirety of that experience is my favorite story.

For folks who don’t know, who was Chol Soo Lee?

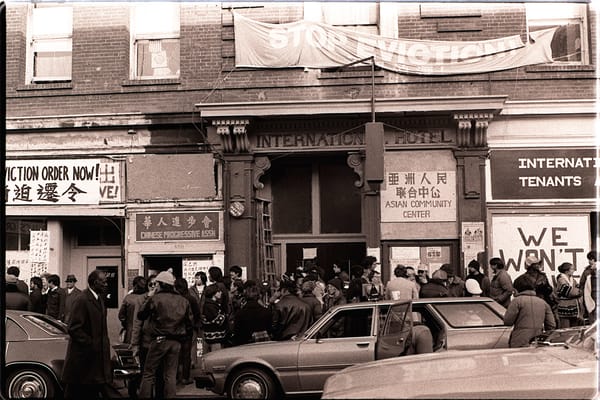

Chol Soo Lee was a Korean American immigrant who was convicted of a murder he didn't commit in Chinatown, San Francisco. He was around 20 at the time. And he wasn't the perfect model-minority immigrant. He got into fights at school and had been in juvenile hall. But he also didn't murder anybody.

What happened was, basically, the description of the person who committed the murder did not match him at all—other than that they were both Asian.

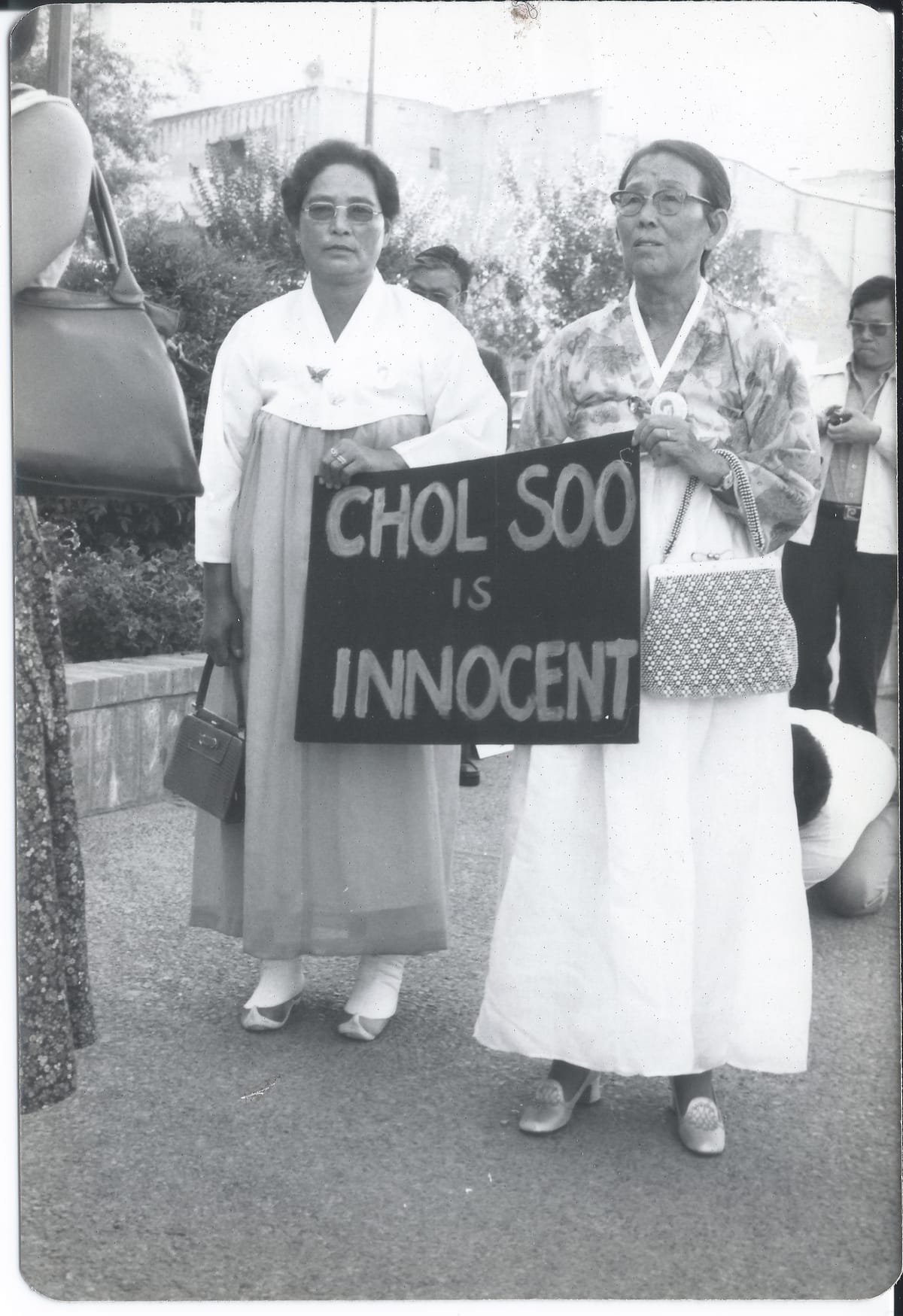

Chol Soo Lee had been suffering alone in prison until a journalist named K.W. Lee, a Korean American immigrant himself, realized there was something fishy going on and took it upon himself to investigate. He was working as the chief investigative reporter for a Sacramento newspaper at the time. His articles inspired one of the first pan-Asian American social justice movements in the 70s—to free someone who had been wrongfully convicted of murder and was serving a life sentence.

When Chol Soo Lee came out of prison, it was such a celebration. But it's not like everything was easy and happy from then on. Because the reality of something like that is: you can't put somebody in such a traumatic situation—he was in prison for over 10 years—and expect him to be the perfect symbol for a landmark movement.

Once he got out of prison, there weren’t any reentry programs, so he struggled a lot. And I think there was a tension between the activists who had worked so hard to free him and the pressures of him not being able to live up to this hero that everyone wanted him to be.

You mentioned you also loved the story behind how the documentary came together.

Yes! So, I'm not part of this behind-the-scenes story. But Julie Ha, one of the co-directors, was my editor at the Korean American magazine KoreAm Journal. Eugene Yi, the other co-director, was a writer there. So I knew them and looked up to them, as a young journalist.

Julie taught me, like, what a nut graf was. [laughs] She's just the best, most supportive editor, and now friend.

And Eugene Yi, I hadn't met him until later, but I loved his stories. I just thought he wrote the most unique, fascinating profile stories.

I had heard from Julie that she and Eugene were working on a film, even though she had no experience making documentaries. And so I remember being like, “Cool!” [laughs]

Julie has said that the seeds of the film were planted at Chol Soo Lee's funeral in 2014, though she didn’t realize it at the time. K.W. Lee got really emotional and angry. Many of the activists were there. They were so sad, because he had died what felt like an untimely death. They had dedicated so much of their lives to get him out, and it felt like a tragic conclusion to his story.

And many of them had this regret about, Could they have done more? And then Julie talks about a moment where K.W. Lee had this outburst at the funeral, and he said, “Why do people not know about this?”

And Julie was like, someone really needs to make a film about the Chol Soo Lee story. So they decided to do it. And as they were making the documentary, I saw the passion. Because it's so hard to make documentaries. I mean, you know.

[Nodding vigorously.]

It's so hard. And for someone like Julie, who had no prior filmmaking experience, she really was just led by a passion and mission—and this obligation I'm sure she felt to her mentor because K.W. Lee was, like, a mentor of hers since she was 18. So I watched the project slowly get people behind it.

For example, they got Sebastian Yoon to be the narrator, voicing Chol Soo Lee. That is such beautiful casting, because he was part of the doc series College Behind Bars. So he was somebody who had personal experience being in prison. And even though it was the producer Su Kim who found him, it turned out that he used to read KoreAm from prison and had once written Julie a letter to the editor!!!!

And I just think there's so many magical things that came together for that film. It got into Sundance. It aired on PBS. It won an Emmy, and now it's going to colleges so young people can learn about it.

But the absolute best part of the behind-the-scenes story of Julie, Eugene, and their whole team making this documentary is that they were able to give some peace to the Free Chol Soo Lee activists—as well as some peace to K.W. Lee before he passed away recently. So I kind of love the whole thing. And I'm just so proud of them.

Oh my gosh, I got chills so many times when you were talking.

[Laughing] Really?

Yeah! Even though I've seen the film, like hearing it through your eyes, it's really beautiful. I didn't know the backstory with Julie.

I remember I saw an early version of the film. I think I was joking with her about it later, that I was incredibly unhelpful, because, you know— at that point of the filmmaking, you're looking for feedback that can help you shape stuff, right? But when I saw the first cut, I was just like, “It's perfect.” [laughs]

And I honestly meant it. I'm sure they changed little things to make it better. But even from that first draft, I was like, “I can't believe you guys pulled this off, because it's so complicated. It's such a complex story.”

I think it's important for Asian American history, but it's also a story I love as, like, a friend watching my friend and mentor accomplish something that seems insane.

And this all comes from a small, grassroots Korean American magazine, KoreAm Journal, which ran for 25 years. I'm not even Korean American, but I wrote for KoreAm and was an editor of the sister publication, Audrey Magazine, which was an Asian American women's magazine.

I love that it comes from ethnic media, you know? K.W. Lee was working for mainstream publications for a while, but he co-founded Koreatown Weekly and launched the English version of Korea Times. Basically, Julie interned at Korea Times, I think, and then she was the editor of KoreAm Journal.

So this all comes from the spirit of community journalism. People started it, because we needed it. And we're gonna tell our stories. We're doing it ourselves. I love stories like that, where there’s a small seed that’s planted that leads to a big blossoming 6, 7 years later.

I love all of that. And I'm so happy that we could capture this meta history. Just watching how it's reverberated through our community, the Asian American journalists, and then the historians, and documentary filmmakers, we're all enmeshed together.

Yeah, it's such an Asian American journalism story. It’s like the power of Asian American journalism, the power of Asian American activists.

I'm so proud of Julie. Even though she's a friend, I do think of her as a mentor and a source of inspiration. The world is so chaotic, right? But I feel like I look at someone like Julie, and her mission is so clear. You can feel that in her work. I just think it's really inspiring.

Beautiful. Lastly, do you have any book or film recommendations for us?

Obviously the film Free Chol Soo Lee. The Asian American Journalists Association and UCLA's Asian American Studies Center also published a book this year called Intersections: A Journalistic History of Asian Pacific America, which also has a chapter about this story. There’s also a forthcoming Asian American studies textbook, also produced by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, called Foundations and Futures: Asian American and Pacific Islander Multimedia Textbook, which also has a chapter on the Free Chol Soo Lee story.

And the documentary College Behind Bars by Lynn Novick, which features Sebastian Yoon.