How the International Hotel Manongs Exemplified Filipino Resistance

Matt Oflas details the legacy that inspires Filipino American activism to this day. Matt is an independent filmmaker, recent USC grad, and member of SIKLAB, a multimedia collective that uplifts the stories of Filipino migrant workers. Though I’d heard about the historic battle for the I-Hotel, I’ve never had the pleasure of listening to someone tell the story with such passion and reverence for their elders. Enjoy!

Tiên Nguyễn: What is your favorite story to tell about Asian American history?

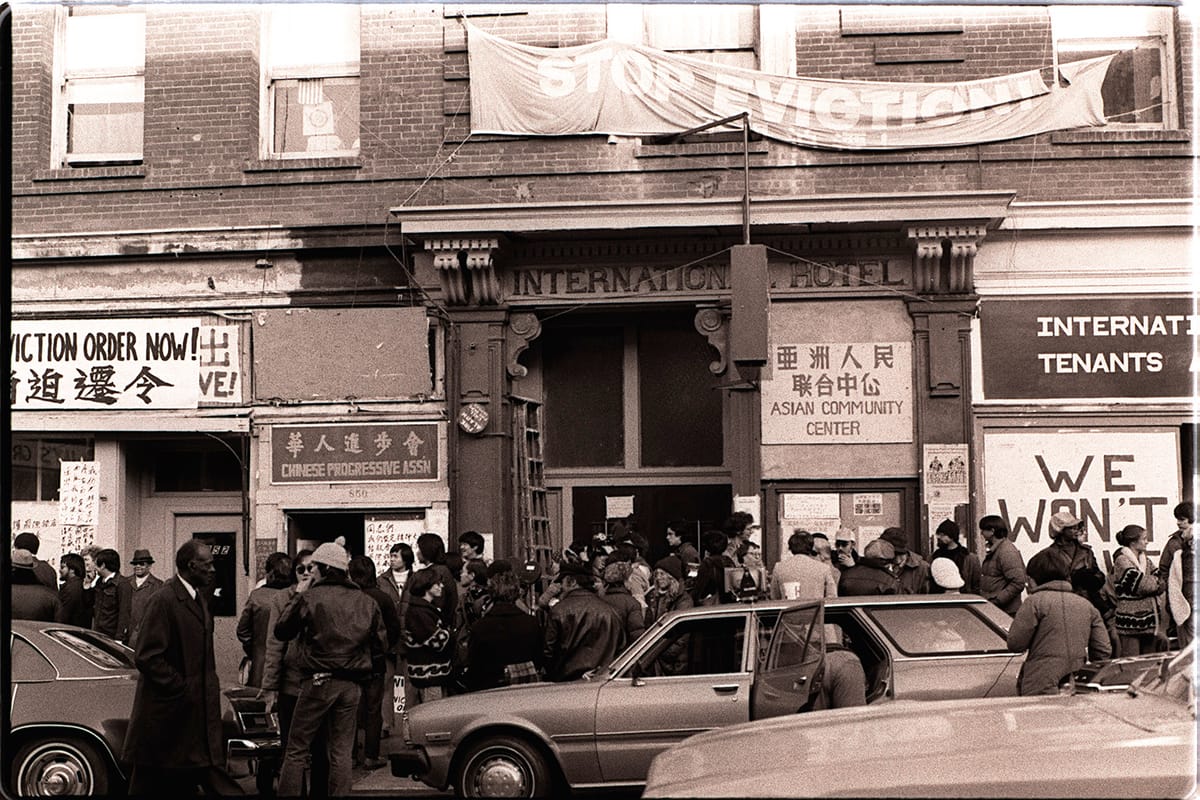

Matt Oflas: Mine is the story of the International Hotel. It was a building in this historic neighborhood in San Francisco, which unfortunately no longer exists, called Manilatown. And it was, like, this ten-block neighborhood full of Filipino-owned businesses and Filipino families—just, like, a little community hub for all these Filipinos. In the 1970s, the International Hotel was the last remaining building of that neighborhood. And there was a whole fight to try to protect the tenants who were facing eviction.

Why were they being evicted?

Around this time—they were calling it the Manhattanization of San Francisco—there was a lot of urban renewal happening, gentrification happening. It was leading to the erasure of these historic neighborhoods like Manilatown. Specifically with the International Hotel, there was a real estate company that was trying to buy it out and develop it into a property.

It was a years-long battle before it came to be the movement that it was in the early 1970s. But for a long time the real estate company was trying to prove that the living conditions there were not great and that they should be evicted. Like, “The building is not up to code.” There was even a fire started in the building, and there was some speculation that the real estate company actually started that to help with their case.

But really it’s a story of urbanization. When it comes to urbanization, the people who pay the price are people who are in low-income housing. People who lived in the International Hotel were primarily Asian Americans, but mostly Filipino Americans and elderly Filipino Americans who had moved to the U.S. in San Francisco to work in the farm fields and then send that money back home to the Philippines. A lot of these elderly residents were men, and they were bachelors, and we call them manongs, as a term of respect. In Filipino culture, that's a term of respect to our elders. They were now in their 60s, 70s, 80s, and it was getting hard for them to find jobs. The hotel was really the only place they could afford to live. It was a really big issue that they were getting forced out because then they would have nowhere to go.

So how did the movement to save the hotel start?

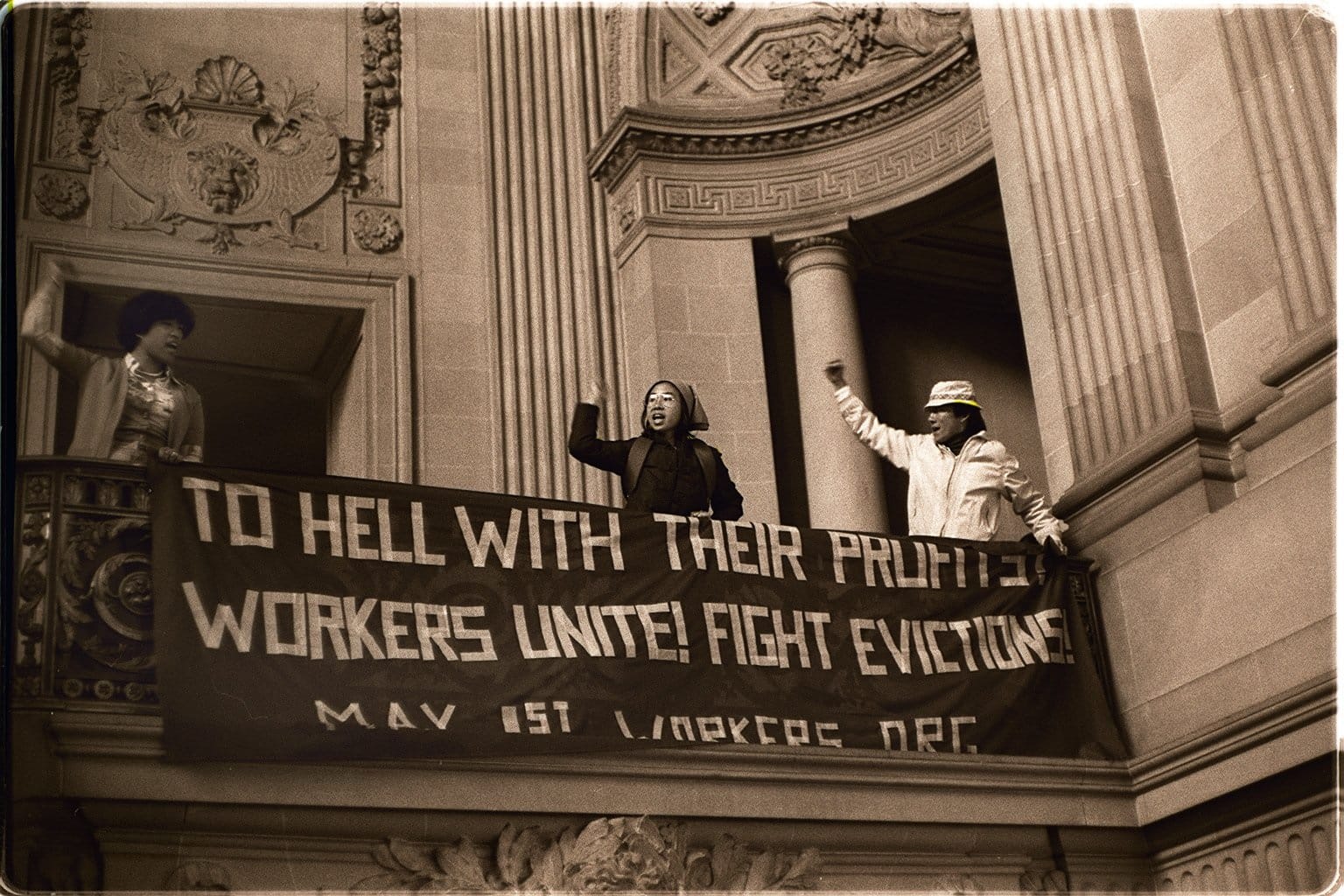

This is my favorite part about this story. You know, eventually this became a really big movement where in the 1970s and in San Francisco, there were a lot of civil rights movements happening.

But first it was the tenants themselves. They actually came together, and said, “Hey, what's happening isn't right. We need to speak out. We need to use our voice.” And so they organized themselves and created, you know, the first version of the International Hotel Tenants Association. Once the tenants started doing that and fighting for themselves, it's like, now people in the community started seeing that and the movement grew from there. And eventually it got to a point where the International Hotel Tenants Association expanded and community members got involved, specifically students from the neighboring colleges like UC Berkeley, San Francisco State University, and a lot of these college students were Filipino Americans.

But there's a generation of Filipino Americans in between the manongs’ generation and this generation of Filipino American college students. This generation of Filipinos, who came to the U.S. after World War II, didn't really move into places like the city. They moved into urban or suburban housing. This wave of Filipino families, their main focus really was assimilation and finding a better life for themselves. They came here, and they saw the manongs who were living in this low, affordable housing, who weren't working anymore. Culturally, they distanced themselves from that, because they're like, “No, that's that's not us. The older generation, they're lazy. Like, we're here and ready to work.” You know, they really bought into the whole American Dream assimilation thing.

And so that generation’s children, who are now the ones coming to the aid of the manongs, like, they hadn't really encountered all of this. They had kind of grown distant from their culture. What happened within these tenants’ associations was eventually each manong was given a caretaker, and usually, a younger caretaker. And so a lot of these Filipino American students were now having these relationships with these older Filipinos. And in doing so, encountered their culture for the first time.

And that's, like, my favorite part of the story, because it's bridging generational gaps. And, like, you're learning about culture, and it's really a story of the older generation inspiring the younger generation, because after seeing the tenants themselves, like, organize and fight for themselves, a lot of these younger Filipino American students became activists themselves.

So what ended up happening after the manongs organized?

So they were organizing for a couple of years, and there was a lot of back and forth with the city. The mayor at that time was showing support, but that fell through. And so, after a lot of back and forth, the whole movement came to a boiling point where eventually they ordered the last eviction notice and said, “This is final.” And the whole community kind of mobilized.

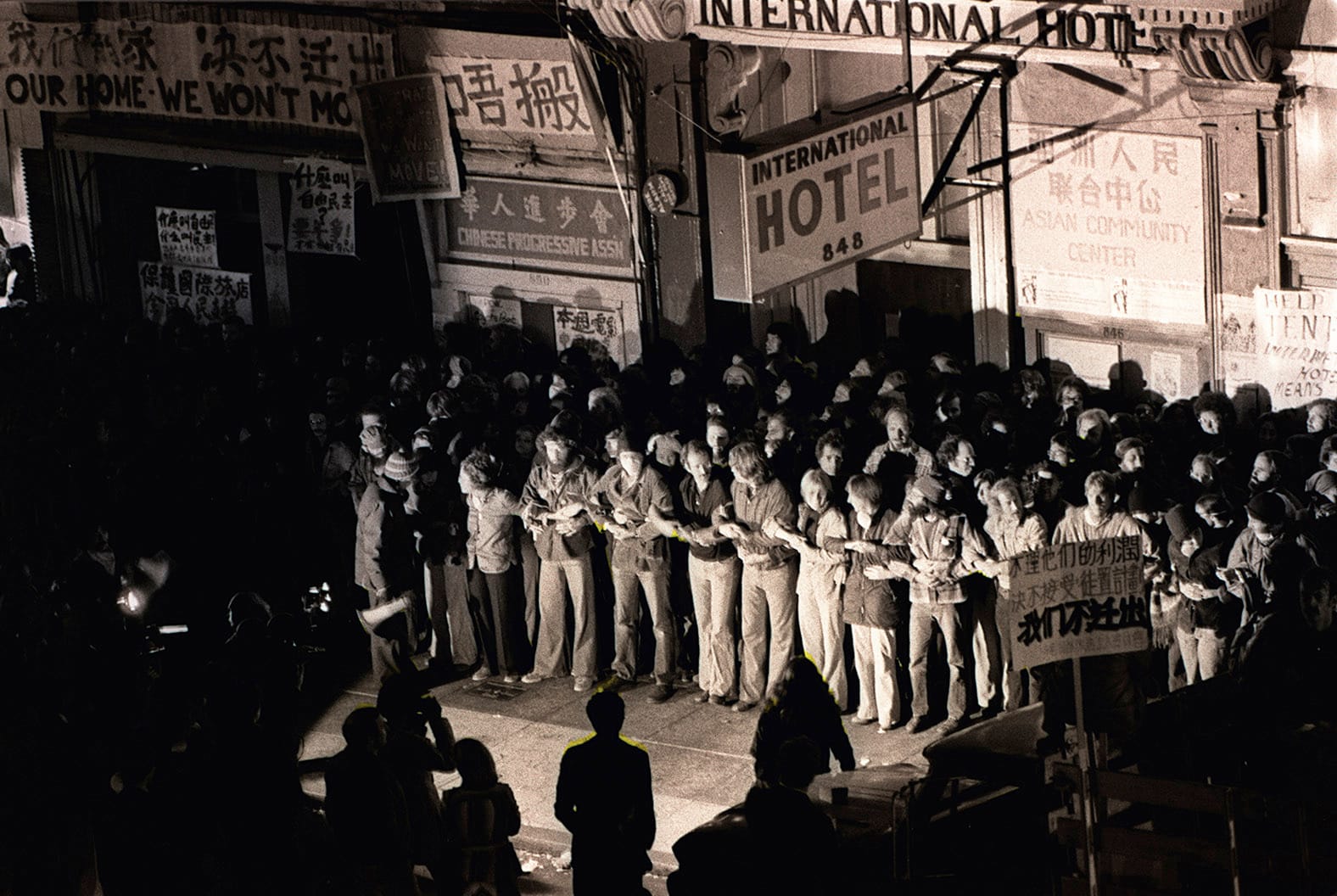

And so, the night that the eviction happened, it was going to be an eviction raid. They were going to send police to forcefully take the tenants out of the building. A group of 3,000 activists showed up and they formed a human barricade. They linked arms around the hotel. And then there were also activists inside the hotel, each of the tenants had someone accompanying them, and they barricaded the doors.

They made as many obstacles as possible to keep the police from coming. The police came, they came in riot gear on horseback, and they were met with resistance. But eventually they were able to force their way in. Unfortunately, and as things started to get a little violent, the tenants themselves actually volunteered to just walk out, because they saw the chaos that was happening outside. They're like, “We don't want people getting hurt because of us.” And so they walked out, and unfortunately, the next day, they completely evicted the building. It is a sad ending. It's kind of like, the salt in the wound was, too, they bought the property and they didn't do anything with it for a while, then they just turned it into a parking lot. And so you're losing affordable housing for a parking structure.

Now it has been bought back. And so they were able to buy it back, and they turned it into affordable housing. And there's a museum on the bottom floor detailing the International Hotel’s history and is now used as a community space. It's a very powerful space.

Even though that story ended in tragedy, what I see is this idea that resistance and fighting for what's right is very inherent in Filipino culture. Since the beginning of our modern history, we've always been struggling against colonial forces, right? Having to fight back and stand up for ourselves, that's a thing that gets overlooked in Filipino culture. I think we're such a welcoming people and other people say things like, “Oh, you go to the Philippines and like, there's some of the happiest and friendliest people, and they're always smiling.”

When I look at this story, I think about how the manongs were the ones who really fought for themselves first, and that inspired other people. You know, that's my takeaway to this, and the fact that, even though they didn't win this battle, they inspired others, and they inspired the next generation. And that battle is still being fought.

I think you’ve alluded to it, but I’ll ask anyway: why do you like this story so much?

The first thing that drew me to this story is that I grew up Filipino American in the San Francisco Bay area, like, basically my entire life. And it wasn't until a couple of years ago that I actually learned about the I-Hotel. That made me want to learn everything I could about it, you know, to make up for all of that.

When I first came across the story, it was in the midst of all the anti-Asian hate crimes, especially against the elderly, and encountering a story where, again, the elderly were being abused and being mistreated and being denied affordable housing and their basic housing rights—it made me see that these issues are still happening. The reason why I love this story the most is, again, the relationship between the manongs and the younger generations, and how they were able to inspire each other and learn from each other. It really is just, like, a story about community. It takes bridging those generational gaps and cultural gaps to really fight and fight for a better future.

And you’re continuing that tradition with your work with the multimedia collective SIKLAB, right? I know y’all recently covered the story of the North Lake Street tenants, who are elderly Filipinos fighting their eviction here in L.A.

Yeah, I'm so grateful that John, another SIKLAB member, brought the Lake Street tenants’ issue to my attention, because I immediately was drawing parallels to the International Hotel. It's very relevant because the Lake Street tenants organized first themselves, and then organizations like Migrante came to their aid.

Thank you so much for sharing this incredible piece of history. Could you leave us with any recommendations for an Asian American history book or film?

I’ll share two recommendations. One of the activists, her name is Estella Habal, has a book called San Francisco's International Hotel: Mobilizing the Filipino American Community in the Anti-Eviction Movement. As well as Curtis Choy's documentary The Fall of the I-Hotel.

Those are two sources that I really pulled from and am actively looking at, because I'm trying to adapt this historical narrative into a film. And so, pulling from those two sources, I've learned a lot. Both sources are firsthand accounts. Curtis and Estella were both involved in the movement, and their main takeaway is really the relationships they were able to have with the manongs, how that was so special, especially now that most of that generation is gone. So preserving their stories is really important.